The International Women’s Day (IWD) or the International Day of Women’s Rights is special this year in the post pandemic era. The theme for IWD 2021 is “Women in leadership: Achieving an equal future in a COVID-19 world”. The aim is to highlight how female leaders have managed the health crisis and to emphasize the important role that women play in the progress and preservation of mankind. The significance of IWD can vary around the world, depending on cultural and social contexts. In ex-Soviet countries, for example, it is simply a day to celebrate and appreciate women. In some Western countries, there are no special celebrations and people are more focused on moving the dial throughout the year instead. In other Western and South Asian countries, protests and marches are organised by women. There is also the aspect of intersectionality and sexual orientations. Feminists in some countries, such as Spain, are strictly focused on women’s rights whereas in others, such as Pakistan, they include racial and sexual minorities in the debate. For an equal future, we need to understand the similarities and the differences in our present so that we can define our common goals. In order to do that, we should have a look at the past.

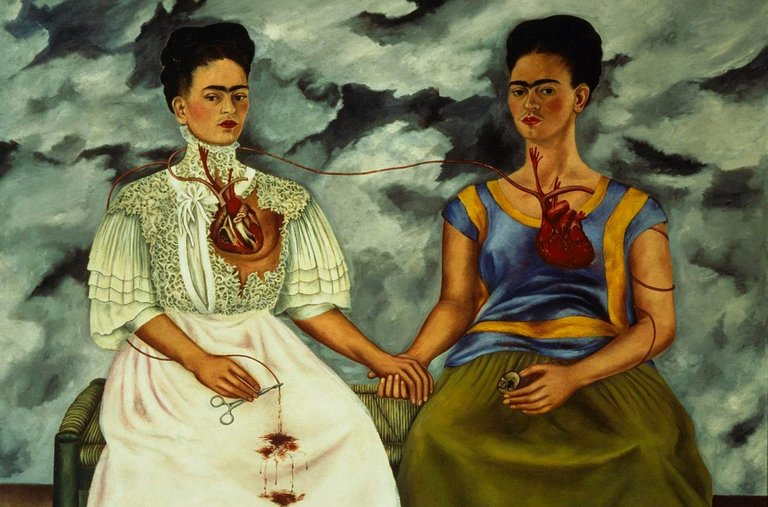

IWD was celebrated for the first time in the beginning of the 20th century in the United States by the Socialist Party of America. It was declared an official holiday in Russia in 1917 after the revolution, brought about by a strike mainly by women. Movements demanding equal rights for women were born much earlier though. While Charles Fourier, the French thinker, is credited with inventing the term “feminism” in 1837, documented demands of women asking for respectful treatment can probably be dated back to the 15th century. Christine de Pizan, in The Book of the City of Ladies (La Cité des Dames, 1405), talks of her sadness after reading texts by an earlier male author claiming that women make men’s lives miserable. For centuries, women were considered to be the property of their husbands. They could not own property, their money belonged to their husbands, and they did not have access to education in general. This social structure survived under tribal and monarchical norms. In the Middle East, the advent of Islam in the 7th century brought about a social revolution in terms of women’s rights. However, in Europe, the concepts of democracy, parliament and citizenship gained prominence much later, around the time of the French revolution in 1789. The French National Constituent Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen. It did not mention any rights of women, even though they had been an astounding force during the revolution, marching to the Versailles along with men. Therefore, in 1791, Olympes de Gouges addressed the Declaration of Rights of Woman and of the [Female] Citizen to the queen, for which she was later guillotined. Around the same time, women in nearby countries such as the UK and Spain, also started speaking up against social injustices and their inferior position in society.

The earliest demands of European and then American feminists revolved around access to education, the right to vote and active participation in the affairs of their countries. In the era where strict social classes divided the people, such as the clergy, nobles and peasants, the demands for women’s rights were in tune with the demands by the lower classes for social and fundamental human rights. Women from these classes worked beside men anyway. However, their social and legal capacity was an urgent priority since they did not have agency over their own person. In fact, the emperor Napoleon through his Code in 1804 officially deprived women of civil capacity. It was not until 1938 that women in France could open bank accounts, sign contracts, own property or enroll in a university. And it was not until 1945 that they could vote, a right that they were “allowed” much later than in some countries in the developed world but still earlier than many others, such as Switzerland, where the law was passed in 1971! Only in 1965 were they able to work without an authorisation from their husband, a right which was granted to women in West Germany in 1977. In Pakistan, on the other hand, women can still not get an emigrant protector stamp for work visa without a No Objection Certificate from their father or husband.

The World Wars changed social and economic structures everywhere. The dearth of human resource in the failing economies of Europe and other war torn countries placed undue demands on women’s reproductive role for quickly rearing a new and strong workforce, while they also worked to rebuild their countries simultaneously. Poverty and lack of education were common and access to health care was spotty. Many women birthed babies while working daily in deplorable conditions whereas others, struggling to survive, resorted to prostitution; hence losing agency over their bodies in both cases. While feminists today, such as those in Spain, raise their voice against prostitution, pornography, surrogacy / rented womb, and violence against women, the agency over their bodies and right to birth control remains a world-wide problem.

The evolution of the discourse about feminism in the regions with Muslim influence has been apparently different. The waves of feminism in recent times seem to coincide globally regardless of the first wave of feminism that came in Europe well before the American suffrage movement, as discussed above. In the Muslim world, however, exemplary figures such as Hazrat Khadija RA and Hazrat Ayesha RA have shaped the discourse. For women in these regions, in principle, civil incapacity has not been as big a concern. As opposed to some other religions, marriage is viewed as a civil contract in Islam therefore, granting her capacity to contract was essential as her consent is necessary for marriage. Nobody has had to fight for the right to own property either, given that women automatically have a share in inheritance. While women’s participation in politics remains low, most Muslim countries such as Pakistan, for example, enfranchised women at the time of creation, whereas in Saudi Arabia, women voted for the first time in 2015.

Nevertheless, in the context of the Indian subcontinent, whatever the dominant religion, there is a unique set of cultural problems in addition to similar problems shared globally by women. Issues such as acid attacks, honour killings, forced and child marriages, and marriages to a tree or the Quran to avoid inheritance disputes, exist mostly in the said region. Some other kinds of oppression, such as female genital mutilation, are unique to other specific Muslim countries. For regions like North and Latin Americas, racial identities introduce a different dimension to feminism.

What is similar globally, though, is the increasing realisation of the role that women can and should play in the advancement of mankind. While much work still needs to be done to achieve gender parity world-wide and while women are still sexually harassed, raped, beaten or killed at the whim of men, they are also making a mark in workplaces and leadership roles. This year, post COVID-19, IWD intends to celebrate the leadership qualities in women. The working woman, whatever the role in her organisation, is important for this conversation. It is she who has taken on the extra unpaid labour during the lockdowns, and it is she who has been at a higher risk of being laid-off. The attitudes about a woman’s work being inferior and less important than a man’s still persist everywhere. Therefore, an effort to converge at a common goal that we should aspire to attain for a better future should encompass addressing the following concerns no matter what the social, cultural and historical background of the region:

- Access to education: Without the alleviation of intellectual poverty, women will never be able to understand their civil rights, take better care of their health and that of their babies, or raise better human beings. In many countries, such as Pakistan, girls’ education even at the primary level is considered unimportant and children like Malala Yousufzai are attacked.

- Closing the wage gap: Among the educated populations, women are systematically less educated than men and therefore, are only able to work for less skilled positions. This implies a lower annual income. Sometimes, their situation as sole breadwinners is also exploited given that the employability of women can vary according to their age and level of education.

- Promoting conducive work environments: Those women who manage to integrate in the corporate workforce can face discrimination and sexual harassment in workplaces. It can also be difficult to juggle between professional and personal life due to the lack of gender balance in unpaid and unseen labour in private spheres. Women inevitably have to take some time off after childbirth but they live in fear of losing their jobs. Despite the laws of a country, many of them find their employment contracts terminated due to their pregnancy, whereas young mothers are not hired easily as recruiters boldly ask illegal and inappropriate questions about childcare arrangements and future family planning.

- Changing negative social attitudes: Day care centres are still looked down upon in many societies. As many organisations globally are setting up childcare centres for their employees, tolerance for working mothers bringing their infants to the workplace may be increasing but the change is slow. Even when paternity leave is compulsory in some countries, researchers think that it may not be sufficient. Women are still ridiculed and shamed for being career-oriented as they are expected to focus solely on their domestic life and children. Such attitudes have brought Pakistan and India at the lowest ranks of Economic Participation and Opportunity gender gap.

Oppression of women the world over is mostly linked to their financial dependence. They often put up with physical, emotional and sexual abuse in offices and homes, and criticism from the society at large, only because they are deprived of the financial ability to take charge. Years of social conditioning still mean that whenever a woman considers ambitions unrelated to bearing children, a tiny voice in her head discourages her from doing so. Strong women and feminists everywhere have only recently been able to break free from such internalised messages. We still have a long way to go before all women can freely chase their dreams without the fear of being reprimanded and harassed, or being treated like a commodity. To achieve that kind of an equal future, we have to choose to challenge our traditions now and follow the voice of present-day feminists and women leaders everywhere.

The author, Aamina Khan, who is also the editor of Ed-watch, is an international polyglot citizen who likes to explore the world differently. A Chartered Accountant by profession, she likes to read and write in various languages as an amateur.